Why Every PeerDB Cloud Tenant Still Gets a Private Postgres

—and why sticking with the “boring” choice lets us move faster

I’m Kaushik Iska, co-founder and CTO of PeerDB (YC S23), now part of ClickHouse and powering Clickpipes. PeerDB’s job is simple to describe and hard to build: we sit between an application’s Postgres and the rest of the data universe, streaming rows out in real time so users can analyze fresh data wherever they like. Inside each PeerDB deployment lives a catalog—a Postgres database that records every pipeline definition, credential, usage counter and a small slice of pre-aggregated analytics for quick dashboards. This essay is about that catalog and, more precisely, about the decision we made to give every customer their own logical database inside it.

Choosing the least-regret tenancy model

When the first paying users arrived, we noticed three obvious ways to share Postgres:

Row-level multitenancy looked cheap but came with shared-statistics nightmares and the ever-present risk of one tenant’s bad query affecting everyone else.

Schema-per-tenant felt tidier until you tally up extension drift,

pg_namespacebloat and global locks that turn ordinary DDL into a convoy.Database-per-tenant promised hard isolation.

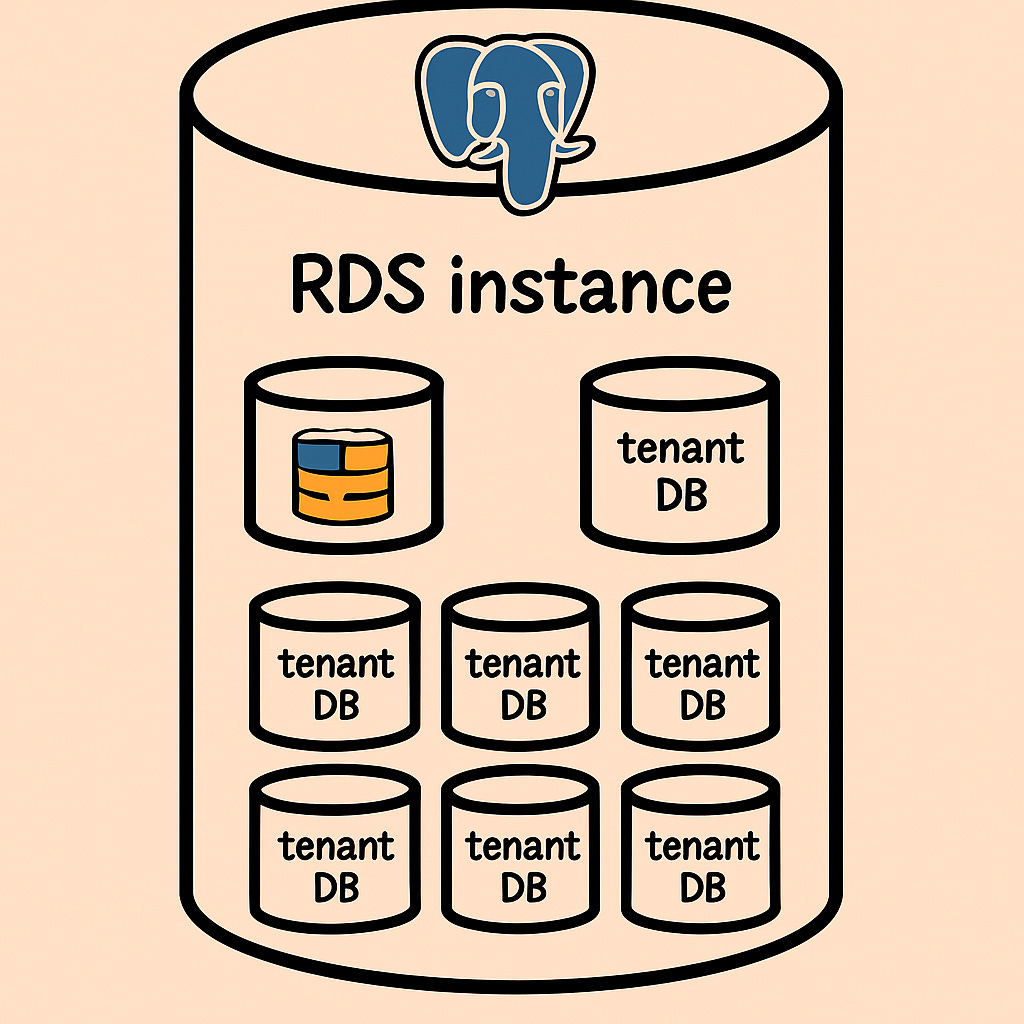

We picked the last option and parked roughly eighty to a hundred tenant databases on a single RDS instance. (We run several of these instances, but the exact count is private.) We briefly considered a physical Postgres per tenant model—true single-tenant servers—but the economics were brutal for smaller customers, and nothing in our workload justified that burn.

What the catalog actually stores

Because PeerDB merely coordinates data movement, not the data itself, the catalog is light. Every write is either metadata (a new pipeline, a rotated secret) or a counter that jumps once per batch moved. We store those counters already rolled-up so queries stay fast; the hottest table is still well under twenty-five gigabytes. If growth ever forces sharding, we’ll know long in advance, and until then we enjoy the luxury of Postgres doing exactly what it has done well for decades.

Shipping changes without roulette

Our schema lives in a refinery migrations folder. During an upgrade the Kubernetes init-container for each service runs the pending migrations against its tenant databases and holds an advisory lock so one long migration can’t block its neighbors. The process is deterministic, self-healing, and—best of all—boringly repeatable.

Observability

We began with Datadog; the swipe-your-card convenience was unbeatable, right up to the moment the bill wasn’t. Today our observability is powered LogHouse and LightHouse.

What has worked in practice

First, a tiny fleet is easy to watch: a couple of RDS dashboards and a Grafana page tell us everything. Second, deep Postgres expertise pays compound interest. When a query plan misbehaves, someone on the team has already debugged that planner corner case in a past life. Third, our open-source posture matches the model; the public PeerDB repository assumes exactly this catalog layout, so what we dog-food is what we ship.

The trade-offs we live with

Postgres connections are fat. In the early days, before we sized instances correctly, we lived in fear of exhausting the pool. Connection pooling and right-sizing bought back margin, but it was a lesson learned the noisy way. And while automation is good, wrangling hundreds of logical databases remains real work—from permissions audits to extension upgrades, there is no perfect autopilot yet.

Still the best deal in town

Could we outgrow this design? Sure—success comes with new scaling puzzles. But the catalog will tell us long before anything combusts, and the escape hatches (read replicas, horizontal shards, even separate servers for large tenants) are well-trodden Postgres terrain. Until that day, every new PeerDB-Cloud customer gets a freshly minted logical database, a clear blast radius, and the quiet confidence that boring infrastructure lets the interesting work happen elsewhere.

See you in the next piece,

Kaushik